Making Heat Visible: Coping with a Hotter World

A person cools off at the Piazza del Popolo, during a heatwave across Italy, in Rome, Italy July 18, 2023. Remo Casilli/Reuters

Recently, a record-breaking heat wave swept across the United States. More than 280 temperature records fell. On just one day—Tuesday, June 25—at least 50 cities hit new highs. Nearly 130 million people were under extreme heat warnings. Even Alaska, a region rarely associated with heat, had to issue advisories.

It’s the kind of story that makes headlines: sweltering cities, overloaded power grids, melting asphalt. But behind the obvious, there’s another story playing out—one that’s harder to see, and easier to ignore.

Extreme heat is what experts call an invisible risk. It doesn’t flood homes or leave behind dramatic debris. But it’s one of the deadliest climate threats we face. And it hits hardest in places that rarely make the news: rural towns, low-income neighborhoods, informal communities—where hospitals may be hours away and power grids are fragile. There’s a Vox article about this very issue—how extreme heat is becoming a growing threat to rural America—that’s worth reading.

This is where the compassion gap shows up. The places most affected by heat aren’t always the ones that make the news. The people most exposed often don’t have the tools—or the visibility—to demand action.

So how do people cope when they’re left to figure it out themselves?

That’s where creative solutions from communities come into play.

In Sichuan, China, a video went viral: two cyclists riding under the sun, their faces wrapped with giant lotus leaves. Improvised, slightly absurd, totally effective. Makeshift sunscreen, courtesy of nature—and TikTok.

In Bikaner, a city in India’s scorching Rajasthan, it’s common to see women riding motorcycles wrapped in layers of colorful scarves and bandanas, like heat-proof cocoons. In 45°C (113°F) weather, fashion becomes survival gear.

A photographer seeks protection from the burning sun on Rod Laver Arena

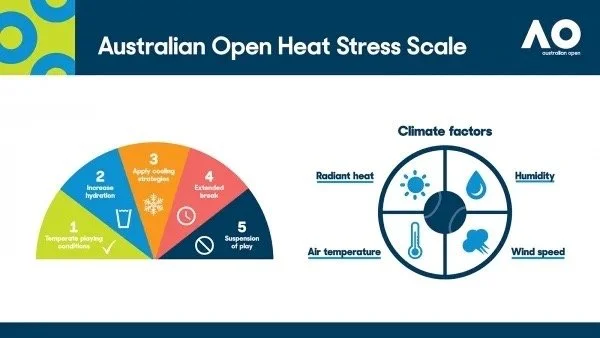

Even elite athletes can’t escape the heat. At the Australian Open, players drench themselves in bottled water, wrap ice towels around their necks, and seek shade wherever they can. Cooling breaks and heat-stress protocols are now part of the game. But the need to improvise isn’t new.

And further back, at the 1960 Formula 1 Grand Prix in Argentina, the solution was even more surreal. As cars sped past, pit crews hurled buckets of water at overheated drivers — a chaotic, splashy reminder of just how far athletes will go when the sun becomes a threat.

From court to riverbank to racetrack, these moments remind us: when infrastructure falls short, people get inventive.

The Right to Shade

We often think of shade as something simple and obvious — a tree or a covered bench. But as cities bake under record-breaking heat, shade has become a precious, sometimes scarce resource.

In many hot regions, access to shade is no longer just a comfort — it's becoming a public health issue. The idea of a "right to shade" is gaining ground, especially in communities where prolonged sun exposure is dangerous and where equitable access to cooling spaces is still out of reach. Not everyone gets to cool down equally.

Take Dubai, where “smart umbrellas” — giant canopies that open and close automatically depending on the sun — are turning public squares into temporary cool spots. It’s a high-tech approach to a low-tech need.

Meanwhile, in many cities worldwide, communities are pushing for more equitable access to shade.

In Australia, councils are deploying shade‑mapping tools and heat‑map‑driven tree‑planting programs. In Penrith, for instance, over 5 000 street and park trees have been planted since 2020 in the most heat‑vulnerable suburbs, and playground shade sails block 97–99 % of UV radiation (aiph.org)

In Brazil, public health initiatives have transformed rooftops into green gardens, reducing ambient temperatures and boosting local resilience during heat waves (NPR, 2025).

These aren’t just quirky stories. They’re snapshots of human adaptation—raw, resourceful, often overlooked. And they reveal something else: a compassion gap. When heat becomes deadly, people improvise not just because they’re inventive, but because systems have failed them.

Why These Stories Matter

These snapshots matter. According to researchers like Paul Slovic, facts alone—especially large-scale statistics—can lead to psychic numbing. We lose the ability to feel the human stakes behind the data. But when we tell stories that show how people live, adapt, and struggle, we shrink the gap between awareness and empathy.

We talk a lot about emissions, temperature targets, global pledges. But if we want to make climate risks visible—and urgent—we need to tell these stories too. The funny ones. The poetic ones. The ones that show resilience, and the ones that show neglect.

Extreme heat isn’t just about temperature. It’s about vulnerability, visibility, and the need to respond not only with infrastructure, but with imagination and compassion.

Because heat may be invisible. But making it visible — through stories, data, and design — is how its impact can be reduced.

If this topic resonated with you, you can also check out a few more stories on invisible risks and risk reminders featured on our website:

Risk Reminders and the Power of Visual Communication

Disaster Risk Reminders: Symbols That Strengthen Awareness and Preparedness