Beachcombers of the Invisible Ocean

By Emiliano Rodríguez Nuesch and María Morena Vicente

We talk a lot about protecting the ocean—its ecosystems, its role in the climate, its wildlife. But most of what happens out there is invisible. Problems begin far from shore, out of sight and easily out of mind. If we want to protect the ocean, we first need a way to see what is happening beneath the surface.

For many of us who don’t work on boats, research vessels, or policymaking tables, the shoreline can be that lens — the simplest, most accessible way to witness what the ocean is enduring and what it needs us to protect.

Every tide carries material across thousands of kilometers and leaves it on the sand. That thin line of debris at our feet is not random; it’s a real-time readout of what the ocean is carrying, tolerating, and struggling with. A beach becomes an archive of the sea: plastic fragments, fishing buoys, ropes, shoes, glass, and objects that once belonged to people a world away.

An entire section of John Anderson’s beachcombing museum is dedicated to artifacts from the 2011 Tohoku

earthquake and tsunami. (Dean Rutz / The Seattle Times)

Once you start reading that shoreline, the risks and impacts become visible. A cracked plastic bottle softened by years of salt and sun is not just trash; it’s a trace of our global consumption. A fishing buoy covered in barnacles may have crossed an entire ocean. A knot of rope fused with shells hints at how long ghost gear drifts, killing silently as it travels. Short clips like this one capture that sense of discovery and connection.

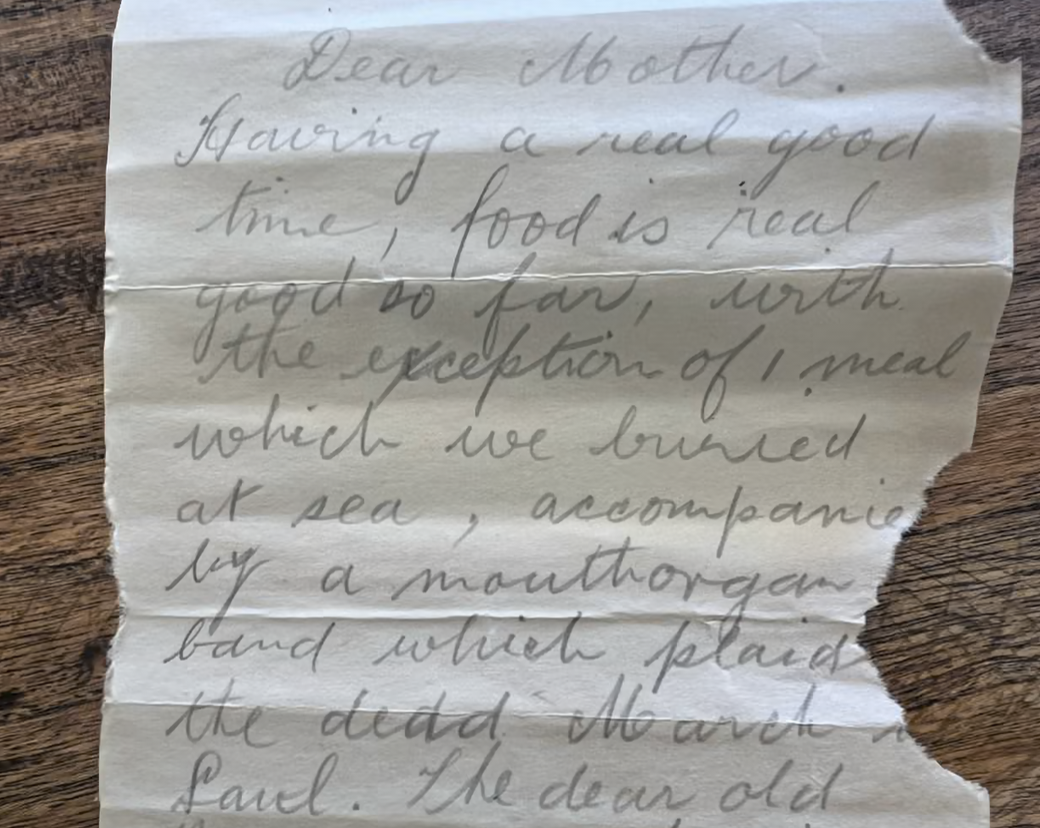

Sometimes the shoreline doesn’t just show pollution and risk—it reveals history. In 2025, storms eroded dunes at Wharton Beach in Western Australia and exposed a glass bottle buried for more than a century. Inside was a message written in 1916 by Private Samuel Miller, a First World War soldier describing seasickness and jokes among his crewmates. A long-lost voice resurfaced because the ocean finally gave it back. You can read that story here: The Guardian – Message in a bottle.

A letter in a bottle written by a soldier to his mother 109 years ago has been found on a beach.Photograph: Deb Brown/AP.

The same process plays out with disasters. After the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, Japanese fishing buoys crossed more than 5,000 kilometers of Pacific Ocean before landing on the shores of Alaska. Beachcomber John Anderson filled an entire section of his museum with these tsunami artifacts, each one a story of loss, displacement, and connection. Emiliano Rodríguez Nuesch’s short film Forget Me Not follows how one of those buoys, found on a remote beach, was traced back to the family whose name was written on it—turning debris into a human bridge between Alaska and Japan.

Pollution writes its own chapters in this archive. Scientists describe the Pacific as a conveyor belt that moves debris, nutrients, species, fishing gear, and sometimes the remnants of people’s lives. Beachcombers now routinely find microplastics embedded in sand, nurdles spilled from global production chains, ghost nets from industrial fisheries, personal items lost after hurricanes or tsunamis, and debris from shipping containers dropped in storms. Clips like this one and this one show how these fragments accumulate on real beaches — and how people are learning to read them.

These objects are not metaphors; they are evidence. They show how interconnected systems work—and fail—in the real world. Beachcombing can be a powerful and simple form of observation. You do not need to be an oceanographer or policymaker to understand what the tide brings in.

If we want to protect the ocean, we need to treat the shoreline as more than scenery. It is an archive and a lens. It shows us what is happening offshore, in supply chains, in disaster zones, and in our own habits. The ocean is already telling us what is happening. The question is whether we are ready to listen.